Ask an anaesthetist

We asked anaesthetists how they explain what anaesthesia is; how they keep patients safe and comfortable; what makes a good anaesthetist; and what they enjoy most about their jobs.

Anaesthesia FAQs

Commonly asked questions about anaesthesia and anaesthetists.

Anaesthetists are highly qualified specialist doctors who provide specialised medical care for you during surgery and other medical procedures, such as childbirth and endoscopy.

Your anaesthetist assesses your health and any medical conditions you may have, and decides on a plan, with you and your surgeon or proceduralist, on the most effective and safe anaesthetic option.

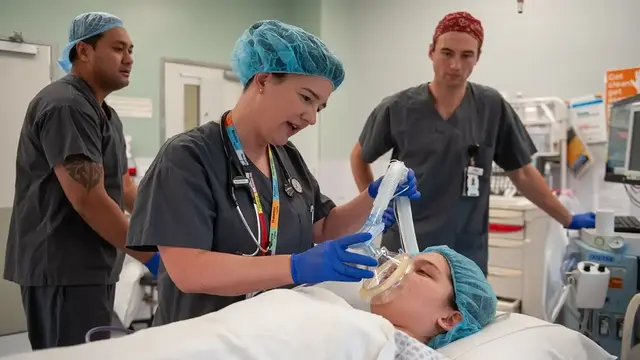

Your anaesthetist uses sophisticated medicines, in carefully calculated doses and combinations, to provide you with either general anaesthesia (making you safely unconscious), sedation, or regional anaesthesia - or a combination of these. This requires highly skilled techniques, of which you are mostly unaware, such as managing your airway and breathing, closely monitoring your blood pressure and circulation, placing nerve blocks and preparing you for recovery to minimise side effects.

Once the procedure is complete, they will continue to look after for you and may prescribe you medication to manage any side effects or post-surgical pain.

Anaesthetists also work in resuscitation, intensive care, perioperative medicine, retrieval, disaster response, and pain management.

Watch this short video for more information on general anaesthesia, or visit our patient information page.

In Australia and New Zealand, the words anaesthetist and anaesthesiologist mean the same thing, although anaesthetist is used more often. You might also hear people say anaesthetic doctor.

The title specialist anaesthetist is protected by law. It can only be used by doctors who have successfully completed the ANZCA training program and who continue to meet high professional standards through ongoing learning and development.

In Australia and New Zealand, only doctors can be anaesthetists. This is one reason why these countries have some of the best surgical outcomes in the world. Almost all hospital procedures that need anaesthesia are managed by an ANZCA-qualified anaesthetist.

Anaesthetists are experts in sedation. Some lighter forms of sedation can be given or supervised by other doctors, but only anaesthetists are qualified to provide deep sedation safely.

Local anaesthesia — which numbs a small area of the body for simple procedures — may also be given by other health professionals, such as dentists.

Anaesthetists are intensively trained specialist doctors. In Australia and New Zealand, they study for more than 12 years to gain the advanced knowledge of disease and surgical complexity they need to keep patients pain free, immobile, and in a carefully controlled state of unconsciousness during complex surgery.

The ANZCA anaesthesia training program is the only accredited specialist anaesthesia training program in Australia and New Zealand. It is designed to develop highly skilled specialist anaesthetists capable of providing exceptional patient care.

After graduating from medical school, doctors must complete at least two years of general hospital work before they can apply for the ANZCA training program. However, most end up completing a third year given the competitiveness of being selected onto ANZCA training.

Training involves a minimum of five years of supervised clinical placements in hospitals accredited by ANZCA to maintain high training standards and safe care. During this time, trainee anaesthetists must study and gain all the knowledge required to make the decisions required to keep you safe. They must pass exams and complete rotations in different settings such as obstetrics; neurosurgery; ear nose and throat; and paediatrics to qualify as a specialist anaesthetist.

All anaesthetists must actively participate in continuing professional development to maintain their specialist registration with Ahpra or MCNZ.

Anaesthetists will work with your surgeon and others to develop a personalised plan for you in the operating room as well as after surgery.

Before your surgery, your anaesthetist will review your health, allergies, medications, and risk factors for complications during or after surgery. They use this information to decide the types and dosages of anaesthesia.

During surgery, they will monitor and support your breathing, circulation, and oxygenation. They will continually determine how much anaesthesia you need and how much pain relief you receive during and after surgery.

After your operation is complete, they will take you to a post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU), where you will be closely supervised until you’re awake, breathing normally, comfortable, and with stable vital signs.

A specialist anaesthetist has the training, knowledge, and experience to design an anaesthesia plan that’s tailored to you. Like pilots, they are experts at keeping you safe and managing any unexpected problems or emergencies that might arise.

Anaesthetists work closely with other doctors — including surgeons, intensive care specialists, and GPs — as well as nurses and allied health professionals. This teamwork helps deliver some of the best surgical outcomes in the world.

Yes. Anaesthesia is very safe in Australia and New Zealand — in fact, these are two of the safest places in the world to have an anaesthetic.

All anaesthetists are highly trained specialist doctors with at least 12 years of medical training. While every surgery or procedure carries some risk, serious side effects are very rare thanks to modern equipment, careful monitoring, and expert preparation.

Your anaesthetist will talk with you before your procedure about your health, any medicines you take, and any allergies you have. They’ll also be happy to answer any questions or concerns you might have about your anaesthetic.

General anaesthesia is often described as “going to sleep” or “going under.” While these are common and easy-to-understand terms — even used by doctors — it’s not the same as normal sleep.

Medically, general anaesthesia is a carefully controlled state of unconsciousness created by anaesthetic medicines. You won’t feel pain or be aware of what’s happening during your procedure. While you’re unconscious, you’ll usually have a breathing tube in place. Your anaesthetist stays with you the entire time, carefully monitoring and managing your heart, breathing, and blood pressure.

Watch this short animated video to learn more about the difference.

It depends on the type of anaesthesia you have.

With general anaesthesia, you’ll be completely unconscious — you won’t feel pain or be aware of anything happening during your procedure.

With regional anaesthesia or a local anaesthetic, you may be awake or lightly sedated while the area being treated is numb.

Under a deep sedation procedure, such as a gastroscopy or colonoscopy, you will be comfortable and likely not to remember anything other than drifting off and waking up.

You can find more information on the different types of anaesthesia in our patient information section.

You will receive specific instructions from your anaesthetist. This often includes stopping eating before surgery, and limiting drinking to small amounts of water, because undigested food in your stomach can cause serious complications (like aspiration, a potentially life-threatening inhalation of stomach contents).

General anaesthesia makes you completely unconscious and unaware during a procedure. You won’t feel pain, and you won’t remember what happened. This is often called “going under” or “being put to sleep.”

Your anaesthetist gives you the anaesthetic medicine through a drip into your vein, sometimes starting with a breathing mask. Drugs such as propofol and gases like sevoflurane keep you safely anaesthetised.

While you’re unconscious, you’ll usually have a breathing tube in place. Your anaesthetist stays with you the entire time, carefully monitoring and managing your heart, breathing, and blood pressure.

Watch this short animated video for more information on general anaesthesia, or visit our patient information page.

Regional anaesthesia numbs a larger part of your body, such as an arm, leg, or the area from the waist down. You stay awake, but you won’t feel pain in the numbed area.

Your anaesthetist carefully injects local anaesthetic medicine — such as bupivacaine or ropivacaine — near the nerves that carry pain signals. Common types include:

Spinal anaesthetic: an injection into the fluid around the spinal cord (often used for caesarean births or hip and knee surgery).

Epidural: medicine given through a small tube in your back (often used during labour).

Nerve block: an injection near a specific nerve to numb an arm, shoulder, or leg.

Watch this short video for more information on regional anaesthesia, or visit our patient information page.

Sedation — sometimes called “twilight sedation,” “conscious sedation,” or simply “a sedative” — helps you feel calm and relaxed. It may make you drowsy or sleepy. Sedation is usually given through a drip into your vein, sometimes with extra oxygen to breathe.

Common medicines include midazolam (to help you relax), propofol (to make you sleepy), and fentanyl (for pain relief). With sedation, you usually keep breathing on your own and may not remember much of the procedure afterwards. It’s often used for smaller procedures such as endoscopies, colonoscopies, or dental surgery.

Local anaesthesia numbs a small area of the body, such as the skin around a wound or a single tooth. You stay awake and alert, but you won’t feel pain in the numbed spot.

The medicine — commonly lidocaine or ropivacaine — is injected directly into the area, or sometimes applied as a cream or spray. Everyday examples include the numbing injection you get at the dentist or when having a skin lesion removed.

It’s normal to feel sleepy as you emerge from anaesthesia and you may also briefly feel a little disoriented. Your throat may feel sore (from breathing tubes), you might have dry mouth, nausea, discomfort or pain in the area that’s been operated on.

Your anaesthetist and recovery staff will stay with you to monitor your breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure. They’ll treat any pain or nausea and make sure you wake up safely and comfortably. You’ll be looked after until you can breathe easily on your own, have stable vital signs, and can communicate clearly.

After a general anaesthetic, you should not drive yourself home. The effects of anaesthesia can last longer than you might feel, and your coordination and reaction times may still be impaired. It's important to arrange for someone to drive you home or use a taxi or rideshare service. If you're unable to arrange transportation, discuss this with your anaesthetist or hospital staff before your procedure.

Interviews with anaesthetists

Patient resources

There are several types of anaesthesia that may be used individually or in combination, depending on the operation.

Anaesthetists are specialist doctors with unique clinical knowledge and skills. They have a major role in the perioperative care of surgical patients.

Having surgery under anaesthesia can be a bit daunting, especially if it’s your first time. But there are a few simple things you can do to get yourself better prepared for your surgery.

There are several types of anaesthesia that may be used individually or in combination, depending on the surgery.

You might not need the care of an anaesthetist when you’re carrying and delivering your baby, but it’s good to know what your options are.

Children of all ages, including newborn babies, may require anaesthesia. We'll take various concerns into account to determine what skills and experience medical staff will require to ensure your child has the best outcomes possible.

Endoscopy procedures, which include gastroscopy and colonoscopy, are frequently performed as day-stay cases.

Most adult heart surgery in Australia and New Zealand is performed for coronary artery disease and heart valve disease.

Joint replacement surgery is a common and effective procedure for relieving disability due to severe joint pain and loss of function.

This information has been developed by accredited specialist anaesthetists to help anyone who is considering cosmetic surgery in Australia or New Zealand. It will help you to understand the risks associated with anaesthesia, and the key questions you should ask before having a cosmetic procedure.

Smokers are at increased risk of respiratory, cardiac and wound-related complications following surgery.

Eye surgery can be performed under eye block, topical anaesthesia or general anaesthesia.

Information on anaesthesia monitoring and other common medical procedures for patients who have undergone axillary surgery, including sentinel lymph node biopsy, targeted axillary dissection, and axillary clearance.

Fellowship of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (FANZCA) is an internationally recognised hallmark of specialists of the highest professional standing.

Is your anaesthetist a FANZCA?

The post-nominals FANZCA can only be used by anaesthetists who have met ANZCA's rigorous training or assessment requirements, and actively participate in life-long learning through our educational activities and programs. Use our fellowship directory to check if your anaesthetist is a FANZCA.

Did you know?

Calling all trainee doctors

Considering a career in anaesthesia?

Anaesthesia is one of the most rewarding and fascinating fields of medicine you can specialise in as a medical graduate. It’s a diverse and dynamic discipline, offering a wide range of research and sub-specialist study opportunities.

Here in Australia and New Zealand, we study for a minimum of 12 years to gain the advanced physiological and pharmacological knowledge we need to keep patients pain free, immobile, and in a carefully controlled state of unconsciousness during complex surgery.

But clinical expertise is only part of being a good anaesthetist. Compassion, confidence, cultural competency, and clarity of mind are also integral to anaesthesia practice. Many of our fellows are engaged in voluntary work in low- and middle middle-income countries; Indigenous health programs; rural and remote communities; and even conflict zones.